A close look at natural language production based on Game of Thrones.

Jon Snow, one of the main characters in Game of Thrones, has the reputation of not knowing much, but he has at least something in common with his comrades: he can communicate. Communicating means being able to understand and/or produce language. Jon Snow may not know who his mother is or what the cognitive mechanisms behind language processing are, but, as any communicating entity, what comes out of his mouth is the result of complex interactions between the different types of language-related resources he acquired in his life.

It is widely accepted nowadays that a language has many different levels of representation that allow us to verbalize the meanings we want to convey. Let us try to decompose the process of one simple sentence utterance:

“I was born in Westeros, I’m the son of Eddard Stark.”

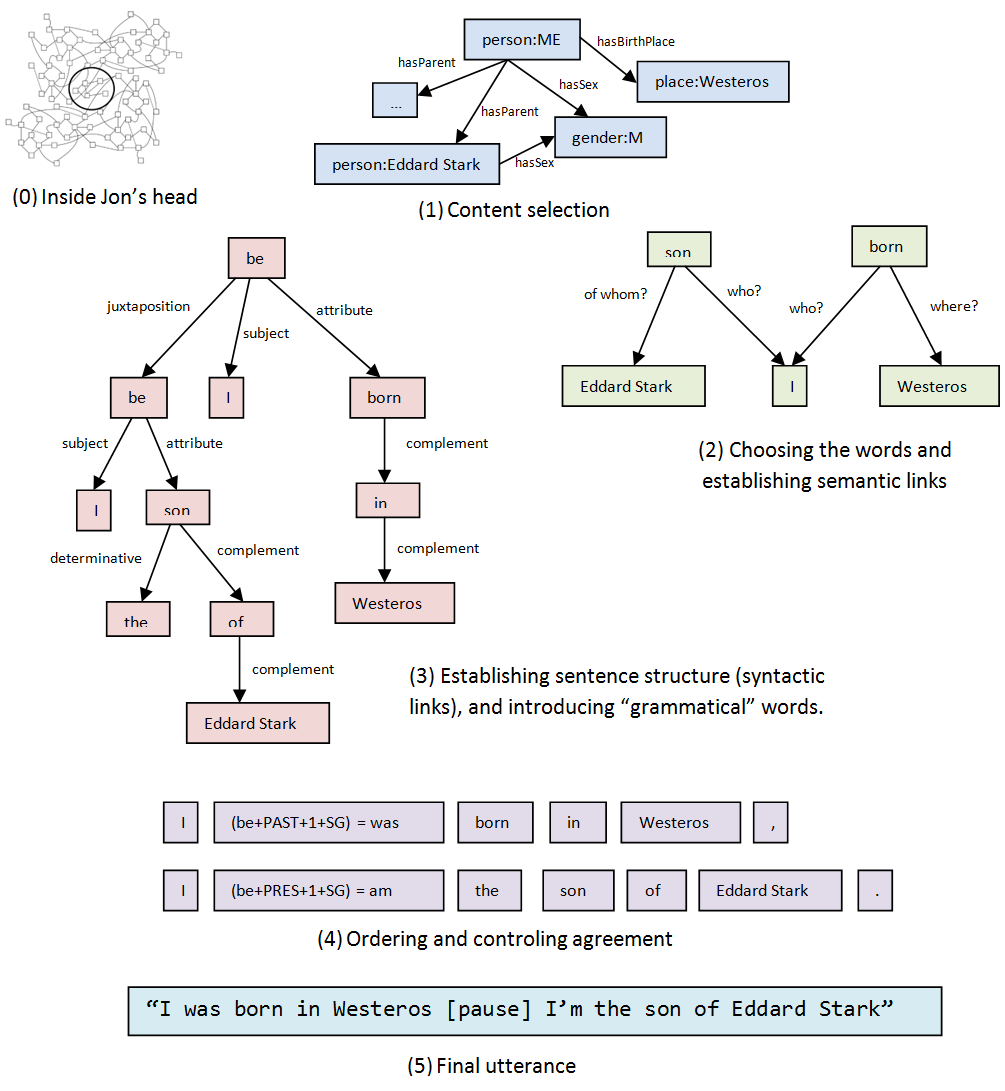

At a very abstract level, we categorize and relate all we know from the world around us: Jon knows that in his world, there are living things, that humans are a type of living thing, and that humans can sometimes have particular relations one with another, for instance, in the case that you share a good part of your genes with someone else. He is conscious of time and space, and knows that in his world, an event happens at a particular place at a particular time, etc. Somewhere in his head, a huge network of entities, facts, events and their respective properties are stored (0). The first thing he does when he speaks is choosing which parts of this network he will realize, that is, he has to select the content of his message (1).

Once this is done, Jon will look for words available in the language he will use –in our case, English- that can convey this content. For example, Jon knows that these two persons who gave you all your genes are called “parents”, and that the male parent is called “father”, and that if X is the father of a male Y, then Y is the “son” of X (2).

Jon knows the rule: if he wants to output a well-formed sentence in English, he has to use a conjugated verb. But unfortunately there is no atomic English verb that he can use to talk about the day he started his existence: he has to use the word “born”.

Fortunately, Jon knows that if he uses “be” with “born”, the problem is solved (French Jean and Spanish Juan could directly pick up the verb naître and nacer respectively). Jon also knows that in a sentence, you cannot just juxtapose “born” and “Westeros”, or “son” and “Eddard Stark”, but that you have to respectively use the prepositions “in” – required by “Westeros” – and “of” – required by “son” – to connect the two elements (3). Jon does not only have networks and rules in his head, he also has many types of dictionaries, including this one that tells him which word requires which other word when used in a combination.

At this point, Jon has all the words he needs for his sentence, but he knows that in English, the word order is important, and that some words have morphological interactions with others: in a declarative sentence, “I” has to be realized before “be”, and “be” has to agree with “I” in person and number (1st person singular). The reason is simple: “I” is the syntactic subject of “be”. Jon may not be aware of what a subject is, or even syntax, but he makes the right choice almost every time. For the same kind of reason, he will put “son” before “of”, and “of” before “Eddard Stark”, while excluding any type of agreement in this configuration (Finnish Jani would know that a preposition requires a particular case on its complement) (4).

But Jon knows even more: once he decides the position of all the words, he knows that if “I” is directly before “am”, it is possible to contract “am” into “‘m”. He also knows when to pause when he utters the sentence, e.g., after “Westeros”, not after “was” (5). At the same time, he chooses a particular intonation in order to have more control over the impact of what he says.

At any step in this pipeline, Jon could have made a wide variety of choices; in other words, there are many ways to realize a pre-defined content, and what Jon said is just one way of saying it. Jon made all these decisions in a fraction of a second. As you can see, Jon knows many things, and so do you!

What does all of this have to to with our work, you wonder? MULTISENSOR’s multilingual automatic text generation system implements the same pipeline as described in this article. On another occasion we will give more details about the different techniques that allow for producing text automatically. So stay posted.

Photo Credit:

- Jon Snow from Game of Thrones by Game Of Thrones Wikipedia